Krishna Namburi Knows that Public-Serving Employees are the Best Source of Innovative, Efficient Solutions

Herocrats Spotlight: Rachael Button Expands the Definition of a Library

Photo credit: Nick Chill, Decorah Public Library

Rachael Button is a Children’s and Young Adult Librarian at Decorah Public Library in Northeastern Iowa, who spoke with us about her experience as a librarian during COVID-19 lockdowns, and the constantly expanding definition of a library.

What is your role at the library?

“I'm the children's and young adult librarian at Decorah Public Library. I handle collection development, programming, and space management for ages 0 through 18. This work is suited to my interests because I get to work with young people at a range of ages and stages. I really like watching the way that kids come into their own, whether they're babies that are learning how to use the stairs, or high schoolers who are asking me for a book that reflects their identity. I feel really honored to be a witness to that, and to accompany them through those experiences.”

Your position has looked really different in the last two years, how have you had to be courageous in the face of a pandemic?

“I think something that takes courage in this job is that it's a lot of responsibility to be entrusted with the programs and the collections for an entire community’s youth. In March 2020, it was not easy or intuitive for me to jump into the new, digital programming world that was asked of me as our community shut down; I'm an educator, and I'm not necessarily an entertainer. I work for a well resourced library, but during those first shutdown weeks, I was on an old iPod, in my house doing story times and editing on an app I downloaded on our spotty-at-best rural WiFi. It was important that families and children continued to see familiar faces during that first lockdown. It was a quick and necessary pivot.

As the library opened up our spaces gradually, we've done a lot of outdoor programming, and tried to support people at whatever comfort level they're at. We are offering in-person programs inside, in-person programs outside, and things that people can do at home. All three have proven to be really popular, and it's been this constant pivot and response as we try to meet people where they're at, and support them.

Something that we have seen is that the things that you do to accommodate people's safety during COVID can also accommodate a myriad of other things that make our work more inclusive. For example: if you’re a person who works a job where you can't take your child to story time at 10:00 AM on a Monday, you can still get a take-home craft bundle. We try to be really seasonal and age diverse in the programs and activities that we put out. I also have some teenagers and seniors who sign up to do our crafts, and I love that! There is an element of being able to do a project at your own pace and in your own space that is valuable beyond the COVID safety concerns that a lot of folks may still need.”

How has your work helped support and build a more just and equitable community?

Rachael and a student on a biking field trip. Photo credit: Nick Chill, Decorah Public Library

“The further in my career that I have gotten, the more I've realized that access is a huge priority to me. The library offers kids the ability to come in and get books, programming, materials, and community engagement, all for free. We have a maker space, and kids can come in and use the materials that we've curated. Access to materials is really important to me, and giving kids access to their community is important too.

We run a biking field trip and a winter field trip program with local partners (Winneshiek County Conservation and Upper Explorerland Safe Routes to School), and that's been an exciting collaboration for me to reexamine what it means to be a library and a public space. My definition of my work goes beyond just literacy. I think that books are an invaluable tool for kids that grants them the ability to see both the world reflected to them, and themselves reflected, in a book. But I also believe in creating free opportunities for kids to connect with public land, and public spaces, that go beyond the walls of the library or the pages of a book.

I’m grateful for the imaginative programming that we've had to do the last couple years because it has expanded the definition of what library programs can look like. I think it also shows that when you put funds to a public place where it can serve a lot of people, it has the ability to make a huge impact. I feel really grateful to get to be a part of that process.”

Outside of pandemic times, have there been any persistent challenges to your work? If so, how have you handled them?

“What can be challenging is that the political environment feels really heavy and we are all just hoping that our world doesn’t implode. One of the things that has taken courage is to trust in my library, to trust in my community, to trust in the choices we've made in terms of building a collection and programs as we continue to center the community in the work. Reading the news can be overwhelming--but in the midst of a lot of uncertainty our local community has been supportive of the library and I believe the work makes a difference.

I think in my particular role, working with children and families, it is my responsibility to develop programming and a collection that reflects the diversity of my community and to stay really positive and to uplift the good things that are happening. While that work is highly important, it can also be very challenging and it often requires constant refocusing. I don't think it's much different than going into the classroom as a teacher and trying to center yourself to be that person who can be responsive to your students. The people that I work with are not my students, but I think being a person who's centered and ready to respond and bring my full energy to the work is really important. That can be a challenge, but I think it's also something that calls us up, right?”

Rachael painting with students at a library program. Photo credit: Nick Chill, Decorah Public Library

Follow Herocrats on LinkedIn to stay updated on new spotlights

Government Employee and Elected Official: Meleesa Johnson’s perspective from two sides of public service

By Piper Wood

Meleesa Johnson is the Director of the Marathon County Solid Waste Department in Marathon County, Wisconsin. She also serves on the Stevens Point City Council representing the fifth district, and was elected the council president by her peers in 2017. Meleesa’s unique role as both an elected city official and government employee in Wisconsin gives her an opportunity to see and cooperate with both sides of state and city government. In her Herocrats interview, Meleesa outlined some of the lessons that she has gleaned from both sides of the public service coin, focusing on what government employees and elected officials can learn from each other.

“There's this intermingling of my professional life and my political life, just because of what I do for a living. But I always have to predicate, ‘I'm speaking as, not as an elected official, I'm speaking here as, a professional working for Marathon County’ or conversely. So I have to be careful to walk that line very, very carefully, but there is so much overlap.”

Despite the challenges of delineating her roles, Johnson has found it helpful to be able see things from the other side.

“From a practical perspective, I find it very helpful in my policy-making because I know what it's like to be staff. Staff needs clear direction. And when policymakers can't make up their mind, or if there's conflict, it's staff that suffers.I know what it's like to be staff when there's no clear direction. As staff, I also understand the challenges of trying to create policy when there is not agreement among policy makers. It gives me insight into those worlds that helped me understand why things move along slowly.”

Colleagues in both positions turn to Meleesa for advice, due to her ‘birds eye view’ of policy work from a dual perspective as a staff member and an elected official.

“It's very, very beneficial because it gives me insight that I think is very helpful in both situations.”

Meleesa has thought a lot about how elected officials and government employees could more effectively work together. Foundationally, she sees a need for greater knowledge of the processes behind government work, and the need to identify the why of staff positions.

“There is sometimes a lack of understanding of the public policy process, even at the local level or the state level or federal level. Well, what underpins your work? What underpins your work are policies that are set forward in ordinance or statute. As staff, you need to understand the policy basis of your work, particularly if you want to get into more leadership roles.”

On the flip side, Johnson sees a knowledge gap for elected officials as well.

“While I was talking about staff needing to understand the public policy process, elected officials also need to understand the public policy process, and understand statutory authority.”

Specifically, Johnson sees City Council as a body with influence, so long as Council understands their role in making decisions and feels empowered to make a decision, without giving into electoral fears.

“Because as I've talked with them, they said, well, it's the mayor's budget, right? No, this is our biggest policy document. And it's our budget. It's not the mayor's budget. It is the council's budget.”

Johnson’s role as both an elected city official and a government employee offers her insight into the integral part that these positions can play in furthering and implementing policy. With these roles in mind, Johnson works as a Herocrat in her community to build capacity and increase knowledge sharing between public servants in her community in Marathon County, Wisconsin.

Have you ever worked in a position that gave you insight into two differing roles? What was this learning experience like?

Herocrats in Action: Jordan Laslett

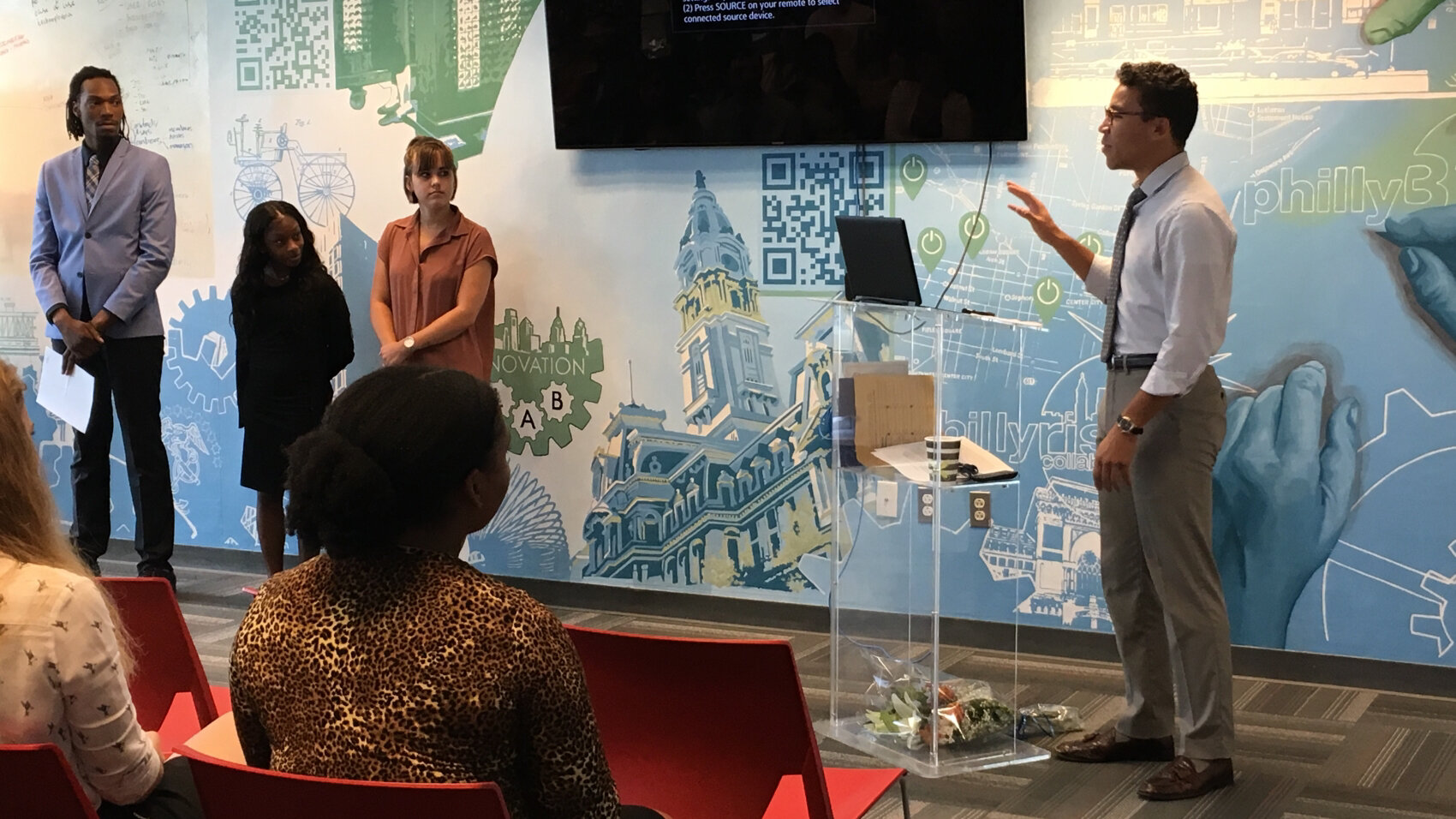

When Jordan Laslett was hired for the summer of 2018 as an AmeriCorps VISTA at the City of Philadelphia, he was energized. A rising senior in college, he knew that this job was a foot in the door in government, where he wanted to make his career. It wasn’t well-paid; he did the math and it would have worked out to about $13,000 for a year’s work. But it paid the bills and allowed him to do innovative work with the community, coordinating a career empowerment fair to teach others how to get jobs in state and local government.

As project manager of this initiative, he got to work with other interns around the City, including those in the Mayor’s Internship Program. Jordan worked side by side with a handful of them to implement the career empowerment fair, which was a success.

They became friends, and throughout the experience, the interns joked about the fact that they were doing the same work, but Jordan was being paid and they weren’t. The dozens of young people who served in the Mayor’s Internship Program were working as volunteers, with no guarantee of a future job in the agency. After hearing their stories over many lunches, Jordan got passionate that they, too, should be paid for their work. He also recognized that the interns who were able to work for free were, in a sense, the lucky ones. How many people with less financial means were excluded from the program?

At the end of the summer, Jordan was left with a few weeks on his contract and nothing left to do on his assigned project. So he checked with his intern friends and asked if they would support him making the case that interns in their program should be paid. They did. With that, he got to work gathering the data he needed to make a surprise presentation on the topic at the big end-of-the-summer event:

“I did not start off by telling my supervisors about it. It was one of those things where it was like, I know this was going to ruffle feathers and I knew that there were a few key folks that knew that I was working on something for the interns but I made it very abundantly intentional to not really expose my hand too much, knowing the Mayor was going to be there, knowing HR was going to be there. At the time I had this streak in me.”

Jordan worried that making a scene at the final presentation could ruin his chances for a career in government, or at least at the City of Philadelphia. But he pressed forward and gathered the data. Meeting with the interns frequently, he passed out surveys that asked about their commutes, their rent and expenses, whether a third party was sponsoring them, and so on. He also did the math on what a paid internship program would cost: he calculated it would only be $80,000 to pay 50 interns minimum wage for 25 hours a week in the summer.

When the big day arrived, Jordan was ready. When he was called up for his presentation, he asked the other interns to come up front and join him. It got immediately uncomfortable in the room when as began to share each other’s stories of working as unpaid interns. For an hour, in front of the city’s senior staff and the public, Jordan presented the data and argued that if they city wanted to live up to its progressive values, it needed to pay its interns.

After the presentation, a journalist from Temple News who had been in the audience approached Jordan for an interview. The next day, he and his pitch for paying interns was featured on the newspaper’s front page. After that, he says, “it was a domino effect and everything moved quickly.” Other media picked up the story, and national advocacy organizations reached out to him to offer support. Within three months, the City of Philadelphia announced it would be paying its interns moving forward, a decision that has been met with celebration locally and nationally. And Jordan, personally, has experienced only positive feedback from city officials and staff.

Of course, at the beginning, he didn’t know it would turn out this way:

“I definitely put my neck out there without realizing it and I think I took a huge risk in terms of having that go nowhere and having nothing to show for the effort.”

It took immense courage for an intern to take this kind of stand. It also took the connection he had with other interns and supportive staff to formulate the proposal.

Today, Jordan is putting those same superpowers of courage and connection into his work as legislative assistant for State Representative Matt Bradford. Working with constituents with urgent needs is tough because it exposes system failings, and how they create pain for real people. Gaps in the systems affect their constituents, who come to him for solutions. Every day he’s faced with difficult situations, such as people potentially losing their homes due to issues like overdue electricity bills.

How does he deal with the stress of the job, and the disappointment of witnessing unjust systems up close and personal every day? He grounds himself in his purpose, and why he chose public service. He takes satisfaction in building relationships with constituents and finding creative solutions for them. He notices and documents opportunities for improvement, then identifies the right time and decision-maker to bring them to for consideration.

But what is his #1 strategy for keeping healthy, sane, and motivated as a Herocrat trying to make systems work better for people? He latches onto the success stories and savors them. Like that time he saw his shot to get city hall interns paid, and he took it.